◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙

Retracting Concessions

The general rule of negotiations is: "If you make a concession, you can’t take

it back." Some people try, however.

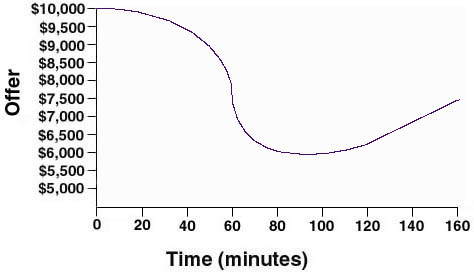

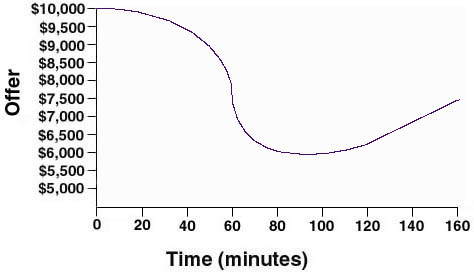

Here, the dealer came down in price from $10,000 to $6,000, and then gradually increased

it back to $7,500.

What is wrong with this strategy?

Generally, the buyer doesn’t believe the price increase. If the dealer would accept

$6,000 a few minutes ago, then he probably will now also. The new $7,500 offer is not

acceptable once a $6,000 offer has been made.

Thus, unless there is some dramatic new information that causes one side to make a less

favorable offer, it is simply not credible to "take back" an offer once it has

been made.

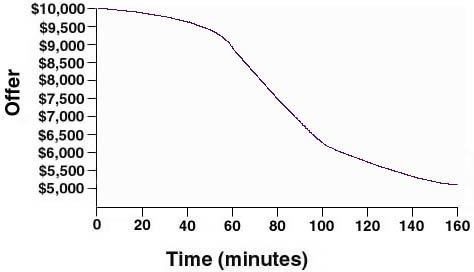

S-Shaped Combination Curves

Many people do not use simple curves -- their curves are some combination of the above

patterns. One such combination is the "S" shaped curve.

Here, the person makes small concessions early in the negotiations. This is followed by a series of large concessions.

The bargaining ends with more small concessions. The motivation for such a curve is typically the desire not to "give away too much too early." Later in the negotiation the motivation appears to be to make the concessions necessary to reach agreement. At the conclusion of bargaining, there may be the desire to get the opponent to make the final concessions as time runs out. This last attempt to get the opponent to make "one more small concession" is sometimes called the "nibbling" bargaining tactic.

This is just one type of combination curve. Can you think of others?

More about "Nibbling"…

Nibbling works best if you have done things earlier that the other side likes. For

example, suppose you had made a proposal earlier that would help the other person make

money (or lower costs) and the other side decided to adopt your idea. Then, when you try

"nibbling," you remind the other side of your earlier idea, so now you would

like him to make a small concession to you.

Example:

You are buying a used car. When visiting the lot, you suggest to the

car dealer that people would find the cars easier to test drive if he wouldn't paint the

price on the driver's side of the windshield in big pink numbers because it interferes

with their ability to see when driving. He likes your idea and decides to paint the price

on the passenger side.

Later, as you are approaching agreement on the price of the car that

you want to buy, you decide to nibble - you want him to fill the car's tank with gas at no

charge. If you remind him of how your earlier idea will increase his sales, then he will

be more likely to give you the tank of gas.

Mismatching, Matching, and More Mismatching

Because people often adjust their concession-making based on what the other side does,

some scholars have noticed a phenomenon called "Mismatching-Matching-Mismatching."

Matching occurs when one side makes similar-sized changes in their offers as the other

side. So if the car dealer is making $500 concessions and you make $500 concessions also,

y'all are making "matching" concessions. Notice that matching may involve large

concessions or small concessions. Just so they are similar in size.

Mismatching occurs when one side makes smaller changes in offers than the other side. So

if the car dealer makes $500 concessions and you make $300 concessions, y'all are making

"mismatching" concessions.

Early in the negotiations

Mismatching often occurs early in negotiations. If the other side is very demanding, we

tend to demand less. If the other side is conciliatory, we tend to demand more. It is

common for one side to make smaller concessions than the other, hoping that the other will

make larger concessions. Sometimes, the negotiators believe it is important to "act

tough" early in negotiations so the other side won't think they can "take

advantage of them." Concessions at this time are usually smaller for one side than

the other side.

There are many reasons for mismatching. Often an issue is more important to one side than

to the other side. The person for whom it is least important is most likely to make the

bigger concessions. Other situational factors may also account for mismatching. For

example, one side may be under great time pressure to settle the dispute quickly. One side

may represent others who are pressuring him not to make too many concessions to the

opponent. Whatever the underlying explanations, with mismatching, one side makes greater

concessions than the other side.

The middle of negotiation

Research has shown that during the middle phase of negotiations, Matching tends to occur.

This takes one of several forms:

1. The negotiator matches the size of the concessions made by the other side. Thus, if you

are matching and the dealer suddenly concedes $1000 on the price, you are likely to

respond by raising your offer by $1000. This is matching the amount of the concession.

2. The negotiator makes concessions that "make up" for not making concessions

earlier in the negotiations. Thus, suppose the dealer has consistently made $500

concessions and has come down from an initial price of $10,000 to an asking price of

$8,000 – his total concessions to this point are worth $2,000. You have conceded

nothing from your opening offer of $5,000. By the middle part of the negotiations, you are

more willing to make some concessions that are worth, in total, $2,000, to narrow the gap

between your respective positions. This is matching the CUMULATIVE amount of the

concessions.

3. You might match the frequency of the concessions. If the dealer makes a new offer every

5 minutes you might sit quietly for the first 30 minutes, but as negotiations progress,

you become more likely to make concessions every time he makes them. You want to

"reward" him for making concessions and you want to "keep the ball

rolling." Matching the frequency of concessions is quite common.

| Review question: | ||

|---|---|---|

|

You have been bargaining for an hour and have conceded nothing. The car dealer decides to make you a generous new offer every ten minutes – the price will drop $500 every ten minutes. If you start making very small concessions ($50) every time he makes one of his ten-minute offers, you are matching: |

||

|

|

The magnitude of his offers. | |

|

|

The cumulative magnitude of his offers. | |

| The frequency of his offers. | ||

|

|

The cumulative frequency of his offers. | |

◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙◙